Projector Reboot: Casting New Light on Book History

After a four-year hiatus, I am thrilled to return to the world of blogging, bringing with me a wealth of new experiences and insights from my tenure as the Director of Book History and Digital Initiatives at the American Antiquarian Society and my return to the classroom at the University of Maryland College Park. This journey has been nothing short of transformative, allowing me to delve deep into the rich tapestry of book history while spearheading innovative digital projects that bridge the past and the present.

To briefly catch up, I served as Director of Book History and Digital Initiatives at the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) from 2019 to 2022. AAS is a research library and learned society located in Worcester, Massachusetts. Since its founding in 1812 by Revolutionary War patriot and printer Isaiah Thomas, AAS has assembled what is today the world’s largest and most accessible collection of books, pamphlets, broadsides, newspapers, periodicals, children’s literature, music, and graphic arts material printed before the twentieth century in what is now the United States. The library’s 4+ million items also include a substantial collection of secondary texts, bibliographies, digital resources, and reference works.

During my tenure at the Society, it was my honor to relaunch the Program in the History of the Book in American Culture (or PHBAC), a scholarly program founded in 1983 and dedicated to fostering research, scholarship, and education in the field of Book History. During this time, I spearheaded digitally curated exhibitions, educational programming, public lectures, and scholarly seminars (including the summer seminars a signature program of the Society).

Part of my duties also included supervising AAS publications. This included managing The Alamanac, the Society’s newsletter; Past is Present, the organization’s blog; Commonplace, a journal sponsored by the Society; Just Teach One and Just Teach One: African American Print, projects that aim to digitize “forgotten texts” and foster collaborative, scholarly efforts to contextualize them for the classroom; THE BOOK (1983-2008), the newsletter of the Program in the History of the Book that I digitized during the pandemic lockdown; and digital exhibitions and resources, which included Black Self-Publishing and Mill Girls in the Nineteenth Century. This work also included books and printed exhibition catalogs published by the Society as well as works published by Oak Knoll and materials held by AAS. The Digital Transgender Archive and Digital Commonwealth were among the external collaborative projects that were started during my time in this position.

All of these projects were collaborative efforts and I am most proud of the relationships I helped foster in this position. These partnerships included work with local organizations including the Worcester Art Museum, the Worcester Historical Museum (WHM), the Worcester Black History Project, and The Worcester Review, as well as national ones like the Rare Book School and the Bibliographical Society of America. At the end of my time in Massachusetts, I was thrilled to see the organization of “Artists in the Archive,” a digital resource that showcased the creative works conducted by creative writers, filmmakers, and visual artists as a result of their time under “the generous dome” during fellowships at the library. Part of this work was later extended and published across two issues of The Worcester Review.

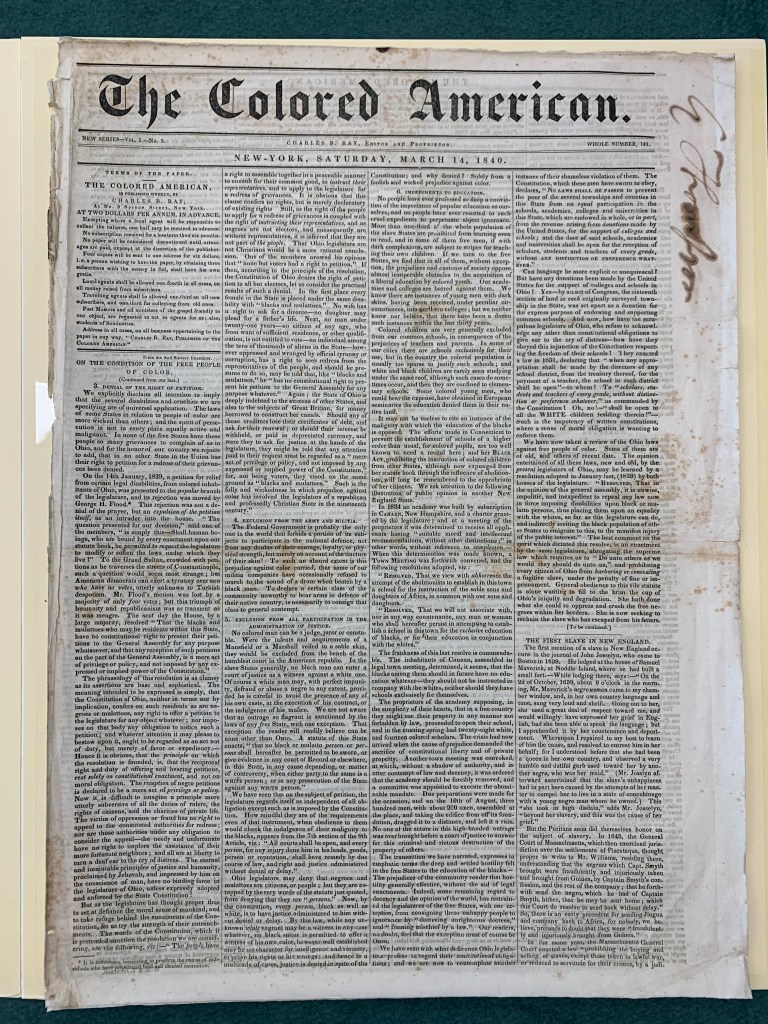

Two years ago this month, I ended my time at AAS by organizing the Program in the History of the Book’s summer seminar: “Black Print, Black Activism, Black Study” led by Derrick R. Spires (Cornell University) and Benjamin Fagan (Auburn University).

This seminar explores the relationship between Black print and Black activism during the long nineteenth century, focusing simultaneously on Black print practices and the ethics of studying Black print and life. How did African Americans use a variety of print forms to share and advance issues of import to Black life in the United States? How did the specific print forms they chose to work in and with influence such issues? We will concentrate on a small number of Black authors (e.g., Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Jarena Lee, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper) and collectives (e.g., colored conventions, committees, newspapers) to trace how they engaged with multiple forms of print. Drawing on the American Antiquarian Society’s extensive collection, we will focus our attention on four primary formats: the pamphlet, the newspaper, the records of the Colored Conventions, and the book.

In addition to offering an opportunity to work closely with primary materials, this seminar will provide participants with an introduction to Black Print Culture Studies. Our archival work will be supplemented by scholarship, some of which may be quite recent, but much of which is foundational to this well-established field. We will also learn from scholars in the field through guest lectures and roundtables. All of the writer/activists we will learn from, be they working in the nineteenth century or the twenty first, require readers to reckon with a series of ethical concerns that remain deeply relevant to our world and our work. The study of African American print culture is also an inquiry into citational practices, the institutional forces that have tended to obscure Black print and elide Black scholarship, and the processes and ethics by which Black study compels us to change these structures. Through our readings and discussions, we will not only explore fascinating materials produced by a community of powerful writers, but also cultivate the practices required for engaging with these communities with an eye towards archives, power, and our relation to them.

Organizing a summer seminar on black print culture presented a vital opportunity to explore the rich tapestry of African American literary and printing contributions. It allowed participants from across the U.S. and the globe to delve into the historical significance of black writers and black-run newspapers and magazines in shaping narratives and advocating for social justice. Such a seminar fostered a deeper understanding of how print media has empowered communities and preserved cultural heritage, offering a platform to discuss contemporary relevance and ongoing challenges in representation and diversity within media landscapes. Meeting scholars, teachers, and students working in this field was such a pleasure and perhaps the greatest end to my time at AAS that I could have imagined.

As I embark on this new chapter, I look forward to sharing the knowledge, stories, and reflections that have shaped my perspective, and I am eager to engage with a vibrant community of readers and scholars once again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.