Daniel Litscho: The Story of a Polish Settler in New Amsterdam

The early history of New York, originally New Amsterdam, is often associated with Dutch settlers, as it was established as a Dutch colony in the early seventeenth century. However, the story of Daniel Litscho reminds us that the diverse fabric of early America included settlers from various European nations, including Poland. Litscho’s life as one of the few documented Polish settlers in New Amsterdam provides a fascinating glimpse into the multicultural dynamics of the early colony and the role that Poles played in its development.

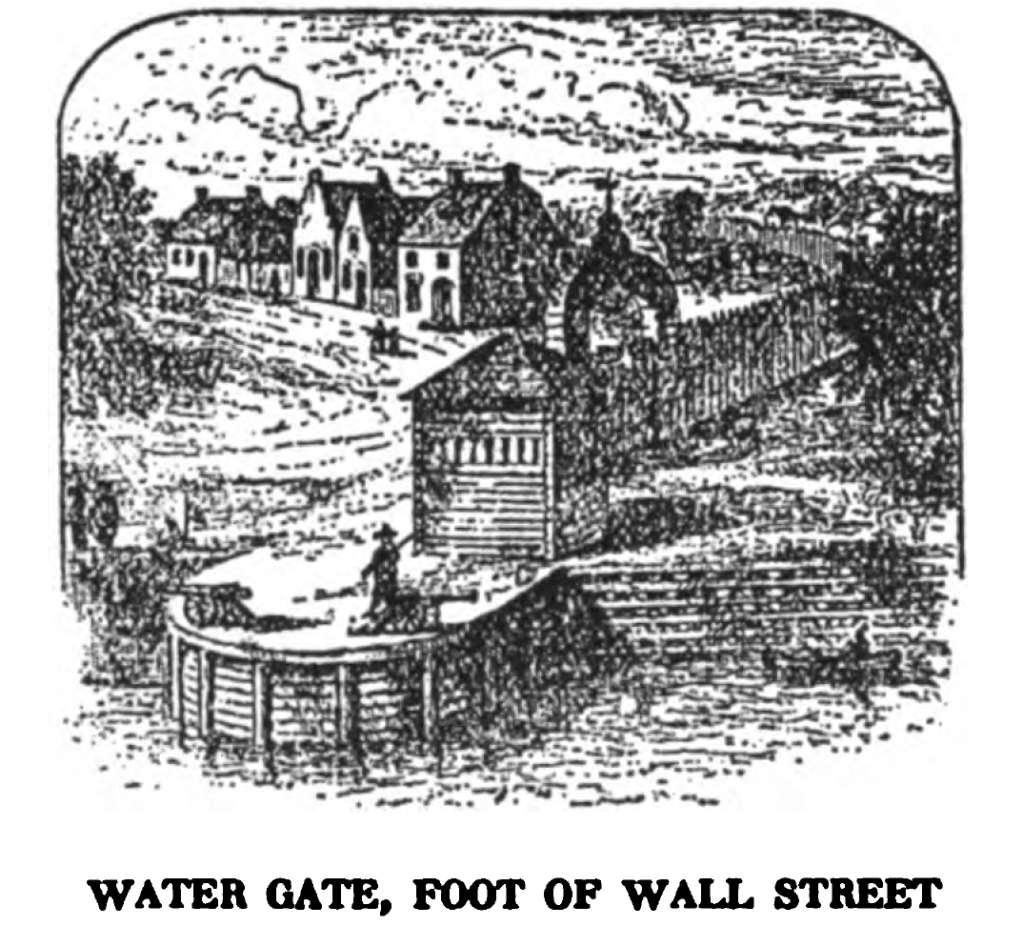

New Amsterdam was founded in 1625 by the Dutch West India Company as the capital of the New Netherland colony. Strategically located at the mouth of the Hudson River, it served as a key hub for trade with Native Americans and European markets. Established as a trading post for the lucrative fur trade, it quickly grew into a diverse and bustling port city and a melting pot of cultures and ethnicities, attracting settlers from across Europe. While the Dutch were the dominant group, New Amsterdam’s population included Africans (both enslaved and free brought by the Dutch as part of the transatlantic slave trade), Germans, Scandinavians, English, and a small number of Poles like Daniel Litscho.

Litscho (1615-1662)—also documented as “Liczko”, “Lischo”, “Litsko”, and “Litchoe”—was born in Koszalin, a city in Pomerania (then part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth). Liczko made passage to the New World as an officer in the Dutch colonial army. His early career took him to Brazil, where he served as a sergeant in the service of the Dutch West India Company, and, by the mid-1640s, he had relocated to New Amsterdam.

Life in New Amsterdam

Although I referred to New Amsterdam as “a melting pot”—at least eighteen different languages were spoken by inhabitants inside the town’s walls—it is important to recognize that the population of the entire colony is estimated at about 500 in 1640 and between 800 and 1,000 in 1650.

Polish settlers left their homes for New Amsterdam in the 17th century for several reasons, primarily tied to economic opportunities and political factors. At the time, Poland was facing internal political instability, economic hardship, and regional conflicts, including wars with neighboring states such as Sweden and the Ottoman Empire. These conditions led some Poles to seek better prospects abroad.

“Prototype View” of New Amsterdam date depicted: c.1651, From Phelps Stokes Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1915, New York Public Library.

New Amsterdam, as a growing Dutch colony, offered economic opportunities in trade, farming, and craftsmanship, and the Dutch were also known for their religious tolerance, which may have also attracted Polish settlers, particularly those of different faiths, such as Protestants or Jews, who faced discrimination or persecution in Europe. The colony’s open and diverse society was appealing to those looking for a fresh start in a new land.

The presence of Poles in New Netherland, or at least the intent of the Dutch authorities that Poles be recruited for the colony, can be seen in several extant documents. In 1646, Pieter Stuyvesant, who had been the governor of the colony in Curaçao, became the governor-general of New Netherland.

Portrait of Peter Stuyvesant (1612–1672). Unknown artist, Attributed to Hendrick Couturier, C. 1660.

In a 1659 letter to West India Company (Westindische Compagnie ((WIC)) Lord Directors, Stuyvesant requested

some good and cleaver farmers, about twenty five to thirty families, and to assist them with a guard of twenty to twenty-five soldiers for two or three years for their protection against the barbarians who are thereabout somewhat strong and bold. That this might be carried out the sooner and with greater celerity and safety, your Honors will please, if possible, to cause that some Polish, Lithuanian, Prussian, Jutlandish or Flemish farmers (who, as we trust, are soon and easily to be found during this Eastern and Northern war), may be sent over by the first ships.

Life in New Amsterdam during the 17th century was not without its challenges. The settlers faced harsh weather, conflicts with Indigenous peoples, and competition with other European powers. Despite these challenges, Litscho and his fellow settlers laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most important cities in the world.

Upon his arrival in New Amsterdam, Daniel Litscho integrated into the colony’s diverse community. As was common among early settlers, he likely engaged in various trades to make a living. The colony’s economy was driven by trade, agriculture, and craftsmanship, with many settlers working as merchants, artisans, or farmers. Litscho’s exact occupation is not well-documented, but he would have been part of the bustling life of the colony, contributing to its growth and development.

Redraft of the Castello Plan New Amsterdam in 1660. North is to the right.

31 x 40 cm Medium: printed map, color wash on paper. John Wolcott Adams and I.N. Phelps Stokes, 1916. New York Historical Society Library, Maps Collection

It is known that Liczko played a prominent role in several military and civic activities in New Amsterdam. He participated in Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s expedition against the Swedes on the Delaware River in 1651 and later led a detachment of soldiers in an important operation that helped liberate the area of Rensselaerswyck from feudal control, laying the groundwork for the future city of Albany.

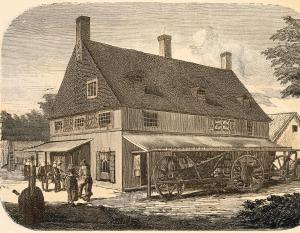

Beyond his military contributions, Liczko became a well-known and wealthy figure in the colony. He also served as a city fire inspector and was involved in the local governance, often participating in the deliberations of the colony’s council. He also established a tavern in New Amsterdam around 1648, which became a key social hub. This might explain his elevated social and economic status in the colony.

“Litcschoe’s Tavern”

Sometime before the year 1648, Litscho established an inn on what is now No. 125 Pearl Street. According to W. Harrison Bayles in Old Taverns of New York,

[t]he tavern seems to have been a good-sized building for it is spoken of as ‘the great house’ … It had at least a quarter of an acre of ground attached to it, and stood back some little distance from the street.

The property was just a three-minute walk from the Fraunces Tavern, Manhattan’s oldest surviving building—and one-time meeting house of the Sons of Liberty during the American Revolution and, later, headquarters of George Washington. It seems like Litscho was an entrepreneur in the sense that he and his family initially lived on a different property closer to the wall and, at least initially, leased this one to Andries Jochemsen, who ran and maintained the property as an ale house and “for many years had lots of trouble with the authorities. He would tap on Sundays and after nine o’clock, and his house was the resort of disorderly persons.”

By 1659, Litscho and his wife, Annetje [also listed in records as Anna and Anneken] moved to a new house as their previous residence “had been condemned by authorities as standing too near the fortifications.” Around the same time, “the great house” establishment closed the family set up a tavern on their new property.

Liczko passed away in 1662, leaving behind a considerable estate. Following his death (at the age of 47), Annetje continued to run the tavern, where she was often referred to as “Mother Litsco” and “Mother Daniel.” Liczko’s influence extended into his family as well; his daughter, Anna, married William Peartree (1643-1714), who would later become the mayor of New York City from 1701 to 1707. Their great-grandson, William Peartree Smith, was the founder of Princeton University.

Litscho’s Legacy

Litscho’s name appears in the records of New Amsterdam, indicating that he was an active member of the community. However, as with many early settlers, documentation is sparse, and much of his life remains a mystery. What is clear, though, is that he was part of a broader narrative of Polish migration to the Americas, a story that began long before the larger waves of Polish immigration in the 19th century.

Daniel Litscho’s story is significant not only because it adds to our understanding of the diverse origins of New Amsterdam but also because it highlights the early presence of Poles in what would become the United States. His life is a reminder that the history of New York, like that of the nation itself, was shaped by a wide array of cultures and peoples.

As New Amsterdam transitioned to British control in 1664 and became New York, the colony continued to grow and diversify. The contributions of early settlers like Litscho helped establish the economic and social foundations of the city. While the larger Polish immigrant communities would not arrive until centuries later, Daniel Litscho and his contemporaries represent the beginnings of the Polish-American experience.

Today, the legacy of early Polish settlers like Daniel Litscho is often overshadowed by the more prominent waves of Polish immigration in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, recognizing the contributions of these early pioneers enriches our understanding of the multicultural roots of America. Daniel Litscho’s life, though only partially recorded, serves as a testament to the resilience and adaptability of Polish immigrants in the New World, and his story is an important chapter in the history of New Amsterdam and the diverse tapestry of early America.

For Further Reading

Babiński, Grzegorz, and Mirosław Frančić. Poles in History and Culture of the United States of America. Zakład Narodowy Im. Ossolińskich, 1979.

Bayles, William Harrison. Old Taverns of New York. Frank Allaben Genealogical Company, 1915.

Brożek, Andrzej. Polish Americans, 1854-1939. Interpress, 1985.

“Daniel Liczko.” World Biographical Encyclopedia, Prabook, https://prabook.com/web/daniel.liczko/2528616.

Grzeloński, Bogdan. Poles in the United States of America, 1776-1865. Interpress, 1976.

Innes, John H. New Amsterdam and Its People. Studies, Social and Topographical, of the Town under Dutch and Early English Rule. With Maps, Plans, Views, Etc. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902.

Haiman, Mieczysław. Polish Past in America, 1608-1865. Polish Museum of America, 1974.

Pertek, Jerzy. Poles on the High Seas. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1978.

Pula, James S., and Pien Versteegh. “Were There Really Poles in New Netherland?” Polish American Studies, vol. 73, no. 2, 2016, pp. 35–55.

Wytrwal, Joseph Anthony. America’s Polish Heritage: A Social History of the Poles in America. Endurance Press, 1961.

You must be logged in to post a comment.