Alexander Karol Curtius: First Teacher in New Amsterdam

In a recent post, I shared a biographical sketch of Polish settler Daniel Litscho and his life in New Amsterdam. In reading for that work, I happened to stumble on another Pole who briefly lived in the Dutch settlement. Although information is even more limited than that about Litscho, I thought it would be interesting to share what I can on the first teacher in New York: Alexander Karol Curtius.

Curtius’ story in New Amsterdam begins in 1658 when the burgomaster and schepens of New Amsterdam (present New York City) sent the following request to the West India Company:

The youth of this place and neighborhood are increasing in number gradually, and most of them can not read and write; but some of the people would like to send their children to a school where Latin is taught, but are not able to do so without sending them to New England, nor can they afford to hire a Latin school-master from there, therefore they ask the Company to send out a fit person, as such master, not doubting that the number of persons who will send their children to such a teacher will from year to year increase until an academy shall be formed . . . For our own part we shall endeavor to find a fit place in which the schoolmaster shall hold his school.

Over a year later, the directors of the Company replied to Governor Peter Stuyvesant, noting that they had finally found a suitable instructor:

How much trouble we have taken to find a Latin Schoolmaster is shown by the fact, that now one Alexander Carolus Curtius, late Professor in Lithuania goes over, whom we have engaged as such at a yearly salary of five hundred florins, board money included; we give him also a present of one hundred florins in merchandise, to be used by him upon his arrival there . . . he shall also be allowed to give private instructions, as far as this can be done without prejudice to his duties . . .

In addition to this salary, Curtius was promised a piece of land “suitable for a garden or orchard.”

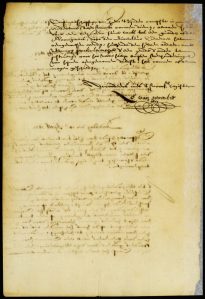

Resolution of chamber at Amsterdam appointing Alexander Carolus Curtius Latin schoolmaster in New Netherlands

Source: New York State Archives. New Netherland. Council. Dutch colonial administrative correspondence, 1646-1664. Series A1810. Volume 13. https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/Objects/54392.

* * *

Little is known about the early life of Alexander Karol Curtius. Records also use Kurczewski and Kurcjusz, highlighting his Polish-Lithuanian origins and the various forms his name took across different languages and regions in Europe, reflective of the fluidity of identity in the 17th century. In various correspondences, Curtius is identified as a nobleman and aristocrat, which is further supported by his admittance into the University of Leipzig in the 1640s. In 1659, Curtius earned his doctorate from the University of Leiden in the Dutch Republic, one of the leading academic centers of the time.

Before he arrived in New Amsterdam in 1659, Curtius was possibly teaching or working as a tutor or academic in the Dutch Republic or elsewhere in Europe. His background as a well-educated linguist suggests that he may have been involved in education or intellectual circles. His decision to move to New Amsterdam appears to have been motivated by a desire to establish a school and promote classical learning in the Dutch colony. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to offer any more insight into his biography before the move across the Atlantic.

Alexander Carolus Curtius (Aleksandras Karolis Kuršius). United States, 1967 by Pranas Lapė From: “Dr. Alexander Carolus Cursius-Curtius”, Čikaga, 1967, p. 23.

After spending over two months at sea, Curtius reached the city of new opportunities in the warm month of July and soon opened a Latin language school for boys on what is today Broad Street. At the time, the Dutch colony had roughly 200 buildings and a population of 1,500. Despite there being some demand for the school from upper- and middle-class parents in the colony, one can imagine the difficulties a new headmaster faced founding a new school and adjusting to colonial life. In the first months of starting the first school in New Amsterdam, Alexander Karol Curtius likely faced significant challenges such as establishing a curriculum and recruiting students in a diverse and developing colony with varying educational needs. Additionally, he had to navigate the logistical difficulties of setting up a new institution in an environment that was still adapting to colonial life and the demands of a burgeoning settlement.

The first school in New Amsterdam would have been a modest yet important institution for the colonial settlement. Housed in a small wooden building typical of the Dutch colonial design, the school likely featured a simple classroom with basic benches or stools for students and a table or platform for the teacher. The curriculum was centered around classical education, with a strong emphasis on Latin and Greek, both of which were critical for reading classical texts and engaging in scholarly pursuits. Religious instruction would have also played an important role, with students studying Christian doctrine and the Bible alongside classical works. Education at this time was primarily aimed at preparing students for roles in religious, legal, or (perhaps) medical fields, although one can imagine a new school like this may have been less grandiose; perhaps Curtius’ focus was on more foundational and practical elements of instruction: basic literacy, arithmetic, and religious studies. His work would have been essential in preparing the colony’s youth for participation in the community’s economic and social life.

The students who attended this school were likely boys from wealthy or prominent families in New Amsterdam, as education was generally reserved for the elite. The class sizes would have been small, perhaps no more than a dozen students at any given time, with boys typically ranging in age from around 10 to 16 years old. Teaching methods relied heavily on recitation, repetition, and memorization, with students expected to memorize Latin grammar, vocabulary, and passages from classical texts.

Discipline in the typical classroom was strict, and corporal punishment was a common method of enforcing order and focus. However, Curtius ran a slightly more lax classroom than the burgomasters had in mind. According to researchers James S. Pula and Pien Versteegh, in his second year in office, the colony’s leaders complained that the professor did not maintain

“strict discipline over the boys in the school, who fight among themselves and tear the clothes from each other’s bodies, which he should prevent or punish.” In response, Curtius asserted that “his hands are bound, as some people do not wish to have their children punished, and he requests that the burgomasters would make a rule or law for the school.”

Before these allegations, Curtius was already becoming a nuisance to colonial leadership. In previous months, Curtius began complaining to his employers about rising prices and a several occasions asked for a raise. Although his students were performing well, his wages remained the same. To offer a more complete picture, at this point, Curtius was not only teaching a classroom of about 20 students each day, but he was also offering private lessons and had set up an office as a physician. He also complained that various herbs, medicinal seeds, and related sundries and supplies had never arrived.

After months of delay, the Directors of the West India Company responded with a short decision that his salary would remain the same “as long as he remains a single man.”

Both parties had had enough. It is unclear if Curtius was fired or if he resigned from the post, but, in June 1661, he departed from New Amsterdam almost exactly two years after arriving in the colony.

After departing from New Amsterdam in 1661, little is definitively known about the later life of Alexander Carolus Curtius. After leaving his post as schoolmaster, records of his movements become sparse. It can be assumed that he returned to Poland or the Netherlands to resume his academic career or work as a tutor or physician, though no conclusive documentation confirms his later activities. His brief tenure in New Amsterdam remains a small but notable footnote in the early educational history of colonial America.

For Further Reading

Cadzow, John F. Lithuanian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland. Cleveland State University, 1978.

Honeyman, A. Van Doren. Joannes Nevius: Schepen and Third Secretary of New Amsterdam under the Dutch, First Secretary of New York City under the English; and His Descendants. A.D. 1627-1900. Honeyman & Co., 1900.

Milerytė-Japertienė, Giedrė, and Lietuvos Nacionalinis Muziejus. A Worldwide Lithuania Our Migration Story. National Museum of Lithuania, 2023.

Siekaniec, Ladislas J. “A Note on Curtius.” Polish American Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 1962, pp. 113–15.

State of New York: Department of Public Instruction: Fortieth Annual Report of the State Superintendent, For the School Year Ending July 25, 1893. Transmitted to the Legislature January 2, 1894. James. B. Lyon, State Printer. 1894.

Wytrwal, Joseph Anthony. America’s Polish Heritage: A Social History of the Poles in America. Endurance Press, 1961.

Wytrwal, Joseph Anthony. The Role of Two American Polish Nationality Organizations in the Acculturation of Poles in America. 1958. University of Michigan, PhD dissertation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.