The American Civil War and December: How Literature Captured the War’s End and Christmas

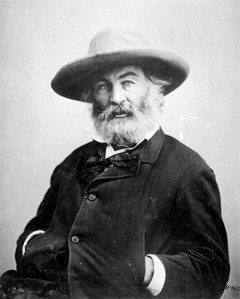

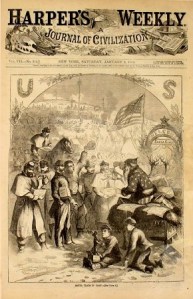

The American Civil War (1861–1865) was a pivotal moment in U.S. history, a conflict that altered the nation’s landscape, both geographically and socially. The war left deep scars on the national consciousness, and its aftermath reverberated through much of 19th-century American literature. Writers like Louisa May Alcott and Walt Whitman responded to the war’s human costs and to the cultural shifts that followed, addressing not only the political turmoil but also how December—symbolizing both the end of the year and the season of Christmas—was framed in the literature of the time.

December, as both a literal and symbolic turning point in the year, has always been a time of reflection. The months of winter often evoke feelings of introspection, and, for Americans emerging from the Civil War, December represented not only a chance to look back on the tumult of the preceding year but also a moment of hope for the future. Christmas, with its associations with peace, goodwill, and family, also offered a respite from the conflict and loss of war. In this article, we will examine how the closing months of the war, particularly the holiday season, were depicted in literary works like Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps, analyzing how December functioned as a mirror for both the literal end of the war and the spiritual recovery of the nation.

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women: The Promise of Family and Healing

Published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869, Little Women by Louisa May Alcott remains one of the most beloved works of 19th-century American literature. The novel, which centers on the March sisters—Jo, Meg, Beth, and Amy—was written against the backdrop of the Civil War and explores themes of personal sacrifice, moral growth, and the ideal of domestic harmony. Alcott’s portrayal of December, particularly Christmas, is infused with a deep sense of both grief and hope, reflecting the collective national experience after the war’s conclusion.

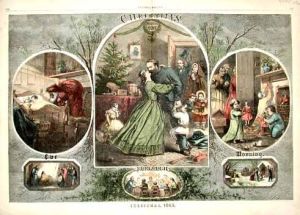

In Little Women, the opening chapter, titled “Christmas,” is set against the harsh realities of war. The March sisters, living in Massachusetts, are struggling with financial hardship while their father, Mr. March, is off fighting in the war. The girls’ mother, Marmee, encourages them to make Christmas a time of giving, even though they are themselves in want. Instead of receiving presents, the sisters decide to use the little money they have to buy gifts for their mother and for their neighbors, reflecting the war’s impact on their sense of sacrifice and duty.

Alcott’s depiction of Christmas as a time of selflessness and familial love aligns with the broader cultural significance of the holiday during and after the Civil War. While the war had torn families apart and caused immense suffering, the Christmas season in Little Women becomes a reminder of the values of generosity, love, and healing. The holiday represents a brief respite from grief, a moment when the family comes together to reclaim a sense of normalcy and peace.

Moreover, Alcott’s portrayal of December in Little Women as a time of restoration is also linked to the war’s end. As the novel progresses, the family copes with the absence of their father and the emotional toll of the war, but by the conclusion, there is a sense of renewal. December, the final month of the year, mirrors this cycle of loss and recovery, suggesting that even after years of suffering, peace and stability can be rebuilt within the home and nation.

Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps: The Complexities of Grief and Redemption

While Alcott’s Little Women presents a sentimental and optimistic view of the post-war period, Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps, first published in 1865, offers a more complex and sometimes somber reflection on the Civil War and its aftermath. Whitman, who worked as a nurse in Washington, D.C., during the war, witnessed firsthand the horrors of battle and the physical and psychological toll it took on soldiers. Drum-Taps, a collection of poetry, explores themes of loss, suffering, and the search for meaning in the wake of the war.

Whitman’s poem “The Christmas Star” is a particularly poignant example of how December and the holiday season are interwoven with the theme of war’s toll on the individual and the nation. The poem reflects a sense of cosmic longing and spiritual yearning, where Christmas, in its connection to the birth of Christ, serves as a symbol of both personal and collective redemption. Whitman writes:

“That is the Christmas star—

It is the heart of the future’s glow,

The light that through the dark

Of long-trodden streets is burning.”

In this sense, Whitman’s depiction of Christmas is not merely an occasion for celebration, but a moment for reflecting on the war’s impact and seeking a path toward renewal. The “Christmas star” serves as a metaphor for a brighter future, but it is also fraught with the sorrow and grief that the war left in its wake. Whitman’s language captures both the despair of the present and the hope for the future, much as the nation, at the war’s end, struggled to reconcile its losses and look ahead.

Another powerful poem from Drum-Taps is “The Wound-Dresser,” in which Whitman recalls his time tending to the wounded soldiers. The poem’s somber tone is filled with imagery of blood and suffering, contrasting sharply with the festive mood typically associated with December and Christmas. In this work, December is not a time of celebration but a reminder of the physical and emotional scars that war leaves on individuals.

Yet, like Little Women, Whitman’s poetry also hints at a broader sense of healing. The final poem in Drum-Taps, “Reconciliation,” moves beyond the pain of war and towards a vision of unity, with an implied call for national healing. The concluding lines of the poem echo a desire for collective recovery, where individuals from both the North and South—once enemies—are reconciled:

“Now the union is established, and now the war is done,

The blood-drops of the Southern soldiers are mingling with those of the North.”

Whitman’s acknowledgment of December’s symbolic significance—of the year’s end and the chance to look forward—suggests that December, with its somber winter backdrop, becomes the perfect moment for this healing to begin.

The Seasonal Shift: December as a Symbol of War’s End and New Beginnings

Both Little Women and Drum-Taps demonstrate how literature from the period following the Civil War reflects the complex emotions of December—its connection to the end of the year, the war, and the season of Christmas. In Alcott’s work, December is a time for families to regroup and rebuild, even in the face of loss. In Whitman’s poetry, December serves as a time for contemplation of the personal and national cost of the war, but also a time to consider the possibilities of reconciliation and renewal.

The end of the war marked a turning point for the United States. The scars of battle and the emotional wounds inflicted upon the country would take years, even decades, to heal. However, the works of Alcott and Whitman show that literature can capture December not just as a time of sorrow, but also as a symbol of hope, renewal, and the potential for collective healing. Whether through the warmth of family love in Little Women or the search for spiritual and national redemption in Drum-Taps, the writers of the Civil War era understood that December, as the year’s closing chapter, held the power to both reflect on past wounds and to imagine a future where those wounds might eventually be healed.

Readings

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women.

Librivox Recordings, Audio Books

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women.

You must be logged in to post a comment.