Dan Waber’s Strings: A Pioneering Work of Digital Poetry

While preparing for my digital textuality lectures this semester, I stumbled across a series of video recordings from 2010–2012—artifacts of an earlier era of electronic literature. Many of the works captured in these videos no longer exist. Defunct organizations, vanished websites, and obsolete technologies have rendered them inaccessible. Among them was Dan Waber’s Strings, a mesmerizing piece of kinetic text that once thrived in the fluid space of early e-lit. Watching it now, frozen in time yet still alive on screen, I was struck by how much of digital literature is inherently ephemeral—shaped as much by its disappearance as by its presence.

In the late 1990s, poet Dan Waber pushed the boundaries of digital poetry with Strings, an innovative Flash-based project that reimagined how words could be presented and experienced. Unlike traditional static text, Strings transformed language into kinetic visual art, with words twisting, stretching, and undulating as though attached to an invisible force. This work not only demonstrated the potential of electronic literature but also exemplified the ephemeral nature of digital artistic expression. Today, Strings is no longer accessible in its original form, a fate that raises questions about the preservation and legacy of electronic literature.

Background: Electronic Literature and Its Context

Electronic literature, often abbreviated as e-lit, refers to literary works that are born digital and rely on computational mechanisms for their full realization. These works often incorporate interactivity, multimedia elements, and algorithmic processes that distinguish them from digitized print literature. The field emerged in the latter half of the 20th century alongside advancements in computing technology and has since evolved through platforms such as hypertext fiction, generative poetry, and interactive installations.

Flash, a now-obsolete multimedia software platform, played a crucial role in the early days of electronic literature, enabling artists and writers to experiment with motion, sound, and interactivity in ways that traditional media could not. However, Flash’s eventual deprecation in 2020 rendered many of these early digital works inaccessible, including Strings. This loss underscores the vulnerability of electronic literature to technological obsolescence and raises questions about how such works can be preserved for future generations.

The Poetics of Strings

At its core, Strings was a deceptively simple yet deeply engaging set of visual poems in which words and phrases moved as though physically manipulated by unseen strings. The project embraced a minimalist aesthetic, with black text on a white background, yet its dynamism and fluidity invited viewers to reconsider the relationship between language and motion.

The poems in Strings played with elasticity and tension, creating a sense of linguistic playfulness that was both mesmerizing and thought-provoking. Words stretched, coiled, and unraveled in ways that challenged the reader’s expectations, forcing an active engagement with the text rather than passive consumption. Unlike traditional poetry, where meaning emerges from careful reading and interpretation of fixed words on a page, Strings made meaning a dynamic process, shaped by movement and change.

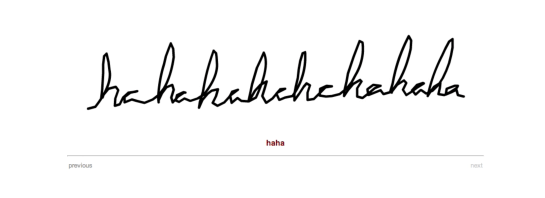

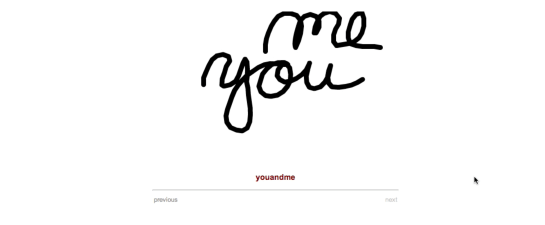

The individual poems within Strings each contributed unique interactions and thematic elements. “Argument” and “Argument2” explored the push and pull of disagreement, visually rendering the way words can strain against each other, refusing to settle into a fixed position. “Flirt” and its continuation, “Flirt (cntd)”, depicted the playful dance of courtship, where words bounced and twisted in an animated back-and-forth exchange that mirrored flirtation itself. “Haha” captured the chaotic nature of laughter, with letters spasmodically shifting and jostling as though overtaken by an uncontrollable giggle. “Youandme” used kinetic typography to explore intimacy and relational tension, enacting the closeness and distance between two entities through its fluid movement. “Arms” was a striking piece that manipulated text in a way that evoked gestures, mimicking the extension and withdrawal of physical limbs, while “Poidog” introduced a more abstract, almost whimsical interplay of text and motion, challenging traditional poetic structure through its visual storytelling.

Waber’s work belonged to a broader tradition of kinetic poetry, where text becomes a moving, living entity rather than a static representation. However, Strings distinguished itself through its seamless fusion of poetry and animation, creating a hybrid form that blurred the boundaries between literary art and digital design. In doing so, it anticipated many of the interactive and animated text experiments that would later flourish in the digital humanities and new media arts.

Legacy and the Challenges of Digital Ephemerality

Although Strings was once widely available and celebrated as a pioneering work of digital poetry, it has since succumbed to technological obsolescence. With Adobe Flash no longer supported by modern browsers, the work has effectively disappeared from the internet, surviving only in archived screenshots and descriptions. This fate highlights a broader challenge facing electronic literature: how to preserve works that depend on proprietary or discontinued software.

The disappearance of Strings serves as a stark reminder of the impermanence of digital art forms. Unlike print literature, which can be physically archived and reproduced, electronic literature often relies on technological infrastructure that evolves rapidly, rendering older works inaccessible unless actively maintained or migrated to newer platforms. Efforts to preserve electronic literature, such as the Electronic Literature Organization’s (ELO) initiatives, have sought to address this issue, but many early digital works remain at risk of being lost forever.

Despite its inaccessibility, Strings remains significant as an early example of digital poetry’s potential. It demonstrated how movement and interactivity could deepen poetic expression, setting a precedent for later works in the field. Moreover, its disappearance prompts important discussions about digital preservation, access, and the responsibilities of both creators and institutions in safeguarding digital cultural heritage.

While Strings may no longer be accessible in its original form, its legacy endures as a landmark in the evolution of digital poetry and a cautionary tale about the fragility of digital artistic expression. As we continue to explore new frontiers in electronic literature, the lessons learned from Strings remain more relevant than ever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.