Can A.I. Create Art? Our Struggle With the Machine in the Studio

This past semester in my “Digital Textuality” course, I posed a deceptively simple question: Can A.I. be an artist? Several students, working independently, centered their final projects on that very topic. Most concluded that A.I. represents a threat to creativity—capable of mimicry but not true originality, of remixing but not authentic making. Yet, almost paradoxically, many of these same students openly acknowledged using A.I. tools like ChatGPT or Grammarly to help them draft analytical essays or clarify complex ideas in other courses. In short, A.I. was welcome as a tutor or assistant in academic work—but regarded as an imposter in the studio.

What’s happening here isn’t just a contradiction in classroom expectations. It’s a window into how we define creativity, authorship, and meaning in an era where machines can generate songs, paintings, stories, and scripts with uncanny fluency. My students’ hesitation reveals a deeply ingrained assumption: that analysis is procedural, while artistry is personal. That the first can be augmented by tools, but the second must emerge from the human soul.

This sentiment, shared by many beyond the classroom, is being tested daily. In the music world, the A.I.-generated song “Heart on My Sleeve,” featuring simulated vocals of Drake and The Weeknd, went viral in 2023 before being pulled over copyright concerns—not because it copied a specific song, but because it sounded convincingly like human artists. In visual arts, a piece titled Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, created by Jason M. Allen using Midjourney, won a prize at the Colorado State Fair’s art competition—prompting backlash from artists who argued it was unfair to compete with algorithmic work. And in publishing, Amazon and other retailers have seen a flood of A.I.-written e-books, including fake travel guides and cookbooks, sparking debate over quality, deception, and the dilution of human storytelling.

Even social media has not been immune. A.I.-generated influencers like Lil Miquela—an entirely virtual Instagram model with brand deals, a personality, and a following in the millions—blur the line between persona and product. These synthetic creators don’t sleep, age, or make mistakes. They also don’t need health insurance. Meanwhile, human influencers find themselves mimicking machine-like aesthetics and productivity just to compete in an algorithmic economy.

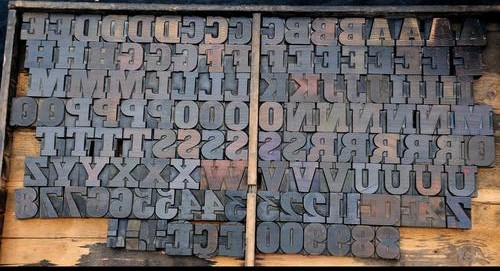

Skeptics—including most of this semester’s students—often argue that A.I. can’t truly create because it lacks consciousness, emotion, and experience. Machines don’t grieve, remember, or long for anything. They don’t know the joy of an unexpected sunset or the quiet grief of personal loss. These are powerful and important distinctions. But we must also recognize that such romantic ideas of creativity overlook how much of human art is the product of training, iteration, and influence. Artists learn by copying, studying, remixing. Great art is rarely made in a vacuum. It builds on existing work and often refines or breaks rules already known.

A.I. reveals just how pattern-based and derivative some creativity already is. The problem isn’t that A.I. generates meaningless art—it’s that it often simulates meaning without having any. The results can be dazzling but hollow: a story that feels like it should matter, a painting that stirs something vague but elusive. This uncanny quality unsettles us because it calls into question where meaning actually resides: in the object, the maker, or the audience?

For educators, the implications are complicated. We ask students to be original, yet we give them templates (often visible in the technical and professional writing courses I also taught this semester). We champion creative voice, yet assign tightly defined structures. The arrival of generative A.I. makes this paradox more visible. If a machine can write a competent sonnet, do we still value the process of struggling through one? If a chatbot outlines your essay, is it a draft or a shortcut?

The response to these questions need not be alarmist. In fact, they present an opportunity to expand how we teach and understand creativity. Instead of insisting that A.I. cannot be creative, we might ask: what kind of collaborator could it become? Already, some artists and writers are using A.I. as a co-creator—prompting it, pushing it, and revising its output to shape new forms. We can challenge students to do the same. Rather than banning generative tools, we can ask students to interrogate them. Assignments could involve revising A.I.-produced work, critiquing its limitations, or integrating it into collaborative creative experiments.

Such an approach forces students to confront their own assumptions about originality and to think critically about the cultural and ethical implications of machine-generated art. They begin to see creativity not as a fixed trait or a sacred act, but as a process—one shaped by tools, context, and intention. By encouraging them to work with A.I., rather than merely resisting or ignoring it, we can prepare them for a future where making is more distributed, more hybrid, and more open to disruption.

A.I. will not replace the artist. But it will force us to think harder about what art is for—and what distinguishes human expression from machine output. The real danger isn’t that the machine makes art. It’s that we stop asking why we do.