Is A.I. the Death of the Lecture—or Its Salvation?

In the age of generative A.I., the traditional college lecture faces a dramatic crossroads. Once a cornerstone of higher education, the lecture now stands accused of being outdated, passive, and ill-suited to a generation raised on YouTube, TikTok, and algorithmic personalization. And with A.I. tools like ChatGPT able to summarize readings, simulate class discussions, and even generate notes from scratch, many educators are left wondering: Is A.I. the death knell of the lecture—or could it be the very thing that saves it?

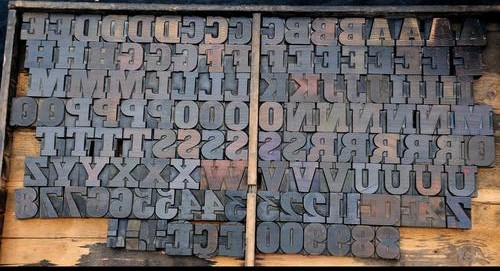

Rooted in medieval university culture, the lecture began as a method of oral transmission—professors read aloud from scarce texts while students copied them down. Over time, it evolved into something more performative: a demonstration of intellectual mastery and an act of public thinking. In the lecture hall, students didn’t just absorb content; they witnessed expertise and synthesis in real time.

But in recent decades, the genre has eroded. Pedagogical research has raised valid concerns about the efficacy of passive listening. Alternatives like seminar-style discussion, flipped classrooms, and active learning environments have surged in popularity. Students—diverse in learning styles, abilities, and attention spans—demand more interaction, personalization, and relevance. Even before the arrival of A.I., the lecture was no longer the undisputed centerpiece of college instruction; it was one mode among many, increasingly out of step with the times.

And yet, the word “lecture” lingers on campus, detached from its original meaning. Students often refer to any class session—PowerPoint walkthroughs, group discussions, even hybrid Zoom meetings—as a “lecture,” regardless of whether it involves a continuous spoken presentation. Some faculty members hold titles like “lecturer” while engaging in far more diverse teaching practices: facilitating workshops, overseeing internships, guiding collaborative projects. The persistence of the term speaks to the lecture’s cultural endurance, but also to its conceptual dilution. It is less a specific format now than a placeholder for academic authority, even as that authority is increasingly exercised through other pedagogical forms.

Now, A.I. threatens to finish what pedagogical reformers began. Why attend a lecture when an algorithm can summarize it in seconds? Why wrestle with dense material when a chatbot can translate it instantly into digestible takeaways? To many students—and perhaps a few administrators—A.I. offers the ultimate convenience: the professor’s knowledge, on-demand and without friction.

But this, ironically, may be what saves the lecture.

If A.I. can handle the repetition, then the lecture must offer something A.I. cannot: depth, presence, provocation. The best lectures were never about information and data delivery. They were about perspective, synthesis, and performance. They told stories. They created a sense of occasion. They made ideas feel urgent, embodied, and alive.

We don’t have to look far to find examples of the lecture’s revival in unexpected places. TED Talks—arguably the most culturally prominent version of the modern lecture—have captivated millions with their compact, narrative-driven delivery of complex ideas. Social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok are full of micro-lectures: bite-sized philosophy, explainers on history and literature, and data storytelling. These formats aren’t dumbing down knowledge; they’re translating it into new idioms. They retain the core of what a good lecture does: deliver insight with clarity, personality, and a compelling voice.

Professors can and should take notes from these models. If students are spending hours watching creators break down the economy or explain moral philosophy in sixty seconds, we must ask: What draws them in? Is it the charisma, the clarity, the relevance, the visual aids? It’s not about abandoning rigor—it’s about adapting form. A well-designed lecture in 2025 might be multimedia-rich, conversational, and segmented. It might include A.I.-generated simulations or interactive polls. It might be posted to YouTube or podcasted for review.

Rather than fight these shifts, professors could use A.I. to amplify what makes lectures powerful. Students might use A.I. tools before class to generate questions or identify themes. Professors might invite students to “fact-check” their claims using language models in real time, introducing an ethics-of-knowledge discussion. In this vision, the lecture becomes a dynamic site of co-creation, not just transmission.

Of course, this reimagining of the lecture isn’t without challenges. Overreliance on A.I. could hollow out critical thinking. There’s a risk of privileging entertainment over depth. And inequities—technological, institutional, and cultural—still persist. Students at under-resourced colleges may not have access to the same A.I. tools that others do. Meanwhile, the cultural shift toward short-form, fast-paced content can encourage a kind of intellectual superficiality that undermines deep engagement.

Yet the larger danger lies in nostalgia. The old lecture—the sage on the stage, the unidirectional flow of wisdom—was already losing relevance. A.I. didn’t cause that; it revealed it. If anything, A.I. offers an opportunity to reimagine the lecture not as a casualty of progress, but as a living genre that can evolve with the times.

A.I. won’t kill the lecture. It will kill the lazy lecture. And that might be the best thing to happen to higher education in decades. The challenge ahead is not to preserve the lecture in amber but to rediscover what made it matter in the first place: human presence, shared attention, and the transformative power of ideas spoken aloud.